Lipoprotein(a): The Silent Heart Killer No One Talks About

Many people believe that if their cholesterol level is normal, their heart is safe. However, statistics show the opposite: heart attacks and strokes often occur in people whose test results do not raise any concerns.

One of the reasons for such “unexplained” cases is lipoprotein(a) or Lp(a) - a little-known but extremely important marker of cardiovascular risk.

Lp(a) is not reflected in a standard lipid panel, so it remains “invisible” even for those who regularly check their cholesterol level. This test is rarely ordered in routine practice - not because it is unimportant, but because it has not yet been included in standard recommendations. As a result, many people with elevated Lp(a) are not even aware of their risk.

Meanwhile, it is one of the most significant indicators: in people with high Lp(a), commonly used statins sometimes have the opposite effect - they can increase its level. It is this hidden factor that often explains why outwardly healthy and active people develop atherosclerosis, heart attacks, or strokes - even with “perfect” LDL.

Who’s Who in the World of Cholesterol

To understand how lipoprotein(a) differs from the usual lipid panel markers, let’s recall how the world of cholesterol is structured.

- LDL - “bad” cholesterol (Low-Density Lipoprotein) - carries cholesterol from the liver to the tissues. If there is too much of it, the risk of oxidation increases, and then it settles on the walls of blood vessels, forming atherosclerotic plaques.

- HDL - “good” cholesterol (High-Density Lipoprotein) - collects excess cholesterol from the vessels and carries it back to the liver for disposal. The higher the HDL, the better the vascular protection.

- Triglycerides (TG) - a form of fat in which the body stores energy. Elevated TG is often associated with excess sugar, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance. High TG increases vascular inflammation and lowers HDL levels.

What Is Lipoprotein(a)?

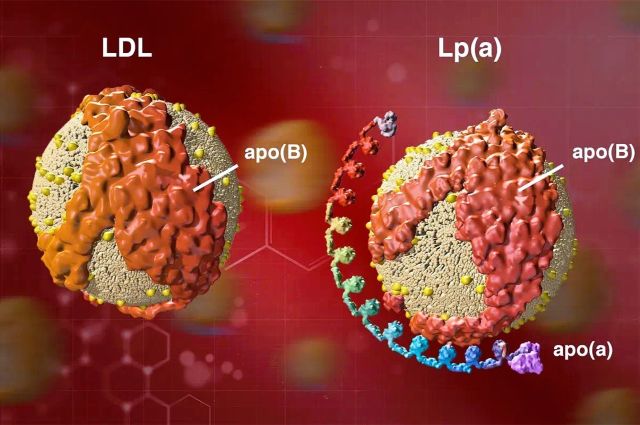

Lipoprotein(a), Lp(a), is structurally very similar to the familiar “bad” cholesterol, LDL, but it has one key difference. If LDL consists mainly of the ApoB-100 protein, Lp(a) has an additional protein attached to it - apolipoprotein(a), or Apo(a). It is this “extra tail” that makes the particle more sticky and pro-inflammatory, increasing the tendency toward thrombosis and vascular damage.

Unlike ordinary LDL, Lp(a) not only contributes to plaque formation but also enhances inflammation and blood clot formation - therefore, it poses a much greater danger to blood vessels.

But the main feature of Lp(a) is that its level is determined by genetics and almost does not depend on diet or lifestyle. Elevated Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for heart attack, stroke, and aortic stenosis, even in people with normal LDL cholesterol levels.

History of Discovery

Lipoprotein(a) was discovered back in 1963 by Norwegian immunologist Kåre Berg.

The scientist noticed that some people had a special type of lipoprotein in their blood, different in structure from the usual LDL.

Already in the 1970s, it became clear that the level of Lp(a) is inherited - it almost does not depend on diet, physical activity, or age. Studies showed that high Lp(a) is directly associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease and other vascular complications.

However, despite the early discoveries, the topic remained on the periphery of medicine for a long time. Several reasons contributed to this:

- For a long time, there were no accurate laboratory tests capable of correctly measuring Lp(a) - they appeared only recently;

- There were no drugs capable of effectively lowering its level; in fact, this issue is still not completely resolved, but more on that later;

- The main focus of cardiologists was on LDL cholesterol - the key target of atherosclerosis prevention for decades, simply because it was easier and clearer to work with.

Only in recent years, with the development of genetic and RNA technologies, has interest in Lp(a) revived. Against the backdrop of significant success in lowering LDL, it became clear that in some patients, heart attacks occur even with ideal LDL cholesterol levels.

This prompted researchers to take another look at lipoprotein(a) as an underestimated but key risk factor that explains the “unexpected” cases of cardiovascular disease in outwardly healthy people.

Dependence of Lp(a) Level on Genetics

The level of lipoprotein(a) almost completely depends on heredity. The main role is played by the LPA gene, which regulates the production of the apolipoprotein(a) protein. In different people, this gene has slightly different structures - and this determines how actively the body produces Lp(a): the “shorter” the gene variant, the higher the level of lipoprotein(a) in the blood.

The genetic influence is so strong that about 90% of the Lp(a) level is explained precisely by hereditary factors. Diet, physical activity, or lifestyle can hardly change this indicator - unlike ordinary LDL cholesterol or triglycerides.

However, although the Lp(a) level is genetically determined, its active production does not begin immediately after birth. In infancy, the liver does not yet fully produce lipoproteins, so the concentration of Lp(a) is low. When the liver matures - approximately at 5-7 years of age - the activity of the LPA gene stabilizes, and the level of Lp(a) reaches constant values.

After that, it remains practically unchanged throughout life.

In women, there may be a slight increase after menopause, which partly explains the rise in cardiovascular risk.

Ethnic differences also exist: in people of African-American origin, the average Lp(a) level is usually 2-3 times higher than in people of other ethnic groups. Nevertheless, elevated Lp(a) remains a significant risk factor for everyone, regardless of origin, sex, or age.

What the Numbers Show

Approximately one in four people has an elevated level of lipoprotein(a). In 5-7%, it exceeds ≈175 nmol/L (≈70 mg/dL) - the threshold at which Lp(a) becomes an independent risk factor for heart attack and stroke. Such a value increases the likelihood of cardiovascular events by 2-3 times compared to the rest of the population.

By itself, high Lp(a) poses a serious danger, but if other factors are added - high LDL, elevated blood pressure, blood sugar, excess weight, or smoking - the risk increases many times over.

It is especially important to remember: elevated Lp(a) combined with high LDL acts as an accelerator of atherosclerosis - blood vessels are damaged faster, and the disease may appear 10-20 years earlier than in people with lower Lp(a) but high LDL.

How, When, and Who Should Be Tested

A lipoprotein(a) test is a simple but very informative test that only needs to be done once in a lifetime. Its level is determined genetically and remains stable, so repeated measurements are usually not required. An exception may be the period of menopause in women, when Lp(a) may increase, or the emergence of new treatment methods capable of lowering Lp(a).

Results can be expressed in two units:

- nmol/L - the most accurate and preferred option, reflecting the number of particles;

- mg/dL - used in some laboratories (for conversion: 1 mg/dL ≈ 2-2.5 nmol/L).

It is especially important to check Lp(a) if:

- there have been heart attacks, strokes, or sudden deaths in the family before the age of 60;

- relatives have been found to have high cholesterol or Lp(a);

- a person has already had cardiovascular events with normal LDL levels;

- there is suspicion of familial hypercholesterolemia.

Since the level of Lp(a) is inherited, it is advisable to examine close relatives - parents, brothers, sisters, and children.

The optimal age for testing a child is 6-8 years, when the indicator is already stable and reflects genetic predisposition. In childhood, no special treatment is required - a balanced diet, regular physical activity, and weight control are sufficient.

If a child has both high Lp(a) and familial hypercholesterolemia, statins can be used from 8-10 years old under the supervision of a specialist.

Testing for Lp(a) is not just an additional analysis, but an opportunity to assess cardiovascular risk in advance. It helps determine how actively LDL should be lowered and which other factors should be corrected to prevent atherosclerosis and its complications. The current goal is not to reduce Lp(a) itself, but to make blood vessels more resistant to its effects and to address all other risk factors.

Awareness of your level is not anxiety - it is a way to act proactively and keep your heart healthy.

What You Can Do Right Now

Nutrition and Natural Support

Nutrition does not directly lower Lp(a), but it helps reduce inflammation, stabilize lipid metabolism, and strengthen blood vessels. The Mediterranean diet works best - rich in vegetables, greens, fish, legumes, and olive oil.

Main principles:

- Minimize saturated fats (fatty meat, sausages, butter);

- Eliminate trans fats (fast food, margarine, processed pastries);

- Add soluble fiber (oatmeal, legumes, apples, flax seeds);

- Include omega-3 sources (fatty fish);

- Limit red and processed meat;

- Use whole, minimally processed foods;

- Include cranberries, blueberries, green tea, and cocoa - they reduce inflammation and improve vascular function.

Natural support

- Coenzyme Q10 - supports energy metabolism and vascular protection (especially when taking statins);

- Acetyl-L-carnitine (ALC) - improves mitochondrial function and fat utilization;

- Omega-3 (EPA/DHA) - reduces blood viscosity and systemic inflammation;

- Magnesium and Vitamin C - stabilize vascular tone and protect the endothelium.

Control of Other Risk Factors

Everything that does not depend on genes is in your hands.

Even if the level of Lp(a) cannot be changed, the overall risk can be reduced by managing other parameters:

- Blood pressure: keep it below 130/80 mmHg;

- Glucose: monitor blood sugar and insulin resistance;

- Weight: reduce abdominal obesity - it is the most dangerous for blood vessels;

- Smoking: complete cessation.

Every corrected factor reduces vascular damage and helps compensate for genetically determined risk.

Environment

Vascular health is influenced not only by nutrition - toxins, mold, and chronic stress also accelerate inflammation and vascular damage.

If there is contact with mold, heavy metals, or chemical pollutants, it is important to eliminate the source and support liver function and antioxidant protection.

Good sleep, physical activity, and reducing chronic stress directly affect endothelial health.

Currently Available Medications

A doctor may recommend the following medications:

- Statins - lower LDL cholesterol levels;

- Ezetimibe - reduces cholesterol absorption;

- PCSK9 inhibitors - lower LDL and partially reduce Lp(a) (by 20-30%).

In severe cases, lipoprotein apheresis (blood filtration from lipids) may be used, usually once every 1-2 weeks in specialized centers; unfortunately, this therapy is not yet available in all provinces of Canada.

New Drugs for Lowering Lp(a)

At present, there is no drug capable of directly and significantly lowering the level of lipoprotein(a). However, in recent years, very promising developments have emerged.

They are based on modern RNA technologies that make it possible to “switch off” the genes responsible for producing proteins involved in forming Lp(a) at the level of messenger RNA (mRNA), so that Lp(a) particles simply do not form.

Several promising drugs are currently being studied, including Pelacarsen (Novartis/Ionis) and Olpasiran (Amgen). According to clinical studies, they can reduce Lp(a) levels by 80-95%.

The results look very encouraging, but these drugs are still undergoing clinical trials, and their appearance on the market is expected in 5-8 years.

The blood test for measuring Lp(a) can be performed through LifeLabs.

Conclusion

Lipoprotein(a) is not a sentence but a call to action. Its level is genetically determined, but knowing about it allows you to take control of your health. Modern approaches - lowering LDL, reducing inflammation, supporting blood vessels, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle - can minimize the risk even with high Lp(a).

Everyone should check this indicator at least once in their lifetime, especially if there have been early cardiovascular events in the family. The earlier the Lp(a) level is known, the easier it is to build an individualized prevention plan and keep the blood vessels healthy.

In the coming years, drugs capable of effectively lowering Lp(a) will become available, but even today, much can be done to protect the heart. The main thing is not to wait for symptoms but to act proactively.